Opportunities abound for HTM professionals to contribute their skills and knowledge to healthcare providers in developing countries

For many healthcare technology management (HTM) professionals, a primary reason for their calling is to help others. That calling often extends beyond the boundaries of their facilities and even those of the United States. Biomeds and clinical engineers across the country contribute their time in all regions of the globe, from Central America, the Caribbean, Haiti, Lebanon, and Kosovo, to the Philippines, Cambodia, Indonesia, India, and Africa. If you have skills or knowledge that would be beneficial to others in lesser developed countries, you should consider saying “yes” to a request for assistance. It’s almost guaranteed that you’ll gain an opportunity to grow on both a professional and a personal level.

The Needs

If you’ve worked in the US healthcare system for many years, it can be a brand new challenge to navigate through other systems where the most basic aspects of supply and demand do not hold true. “All of the rules and norms we know in the United States go out the window. You have to revert back to your most basic knowledge and figure it all out again, like when you started in your career,” says Patrick Lynch of Global Medical Imaging in Charlotte, NC.

Lynch works with the Heineman Foundation of Charlotte. The organization has partnered with the Carolinas HealthCare System and established the International Medical Outreach (IMO) program. With support from foundations, firms, and individuals, the IMO program provides equipment and supplies donations to clinics and hospitals worldwide. Its primary interest, however, is in Central American countries such as Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. “They receive decommissioned equipment and lots of medical supplies, beds, and furniture, and then decide what is needed and sustainable in the countries they are active in,” Lynch says.

Obviously, HTM professionals in the USA and Europe face a lot of challenges, but their counterparts in less-developed regions must also deal with their own unique set of issues. This includes limited technical resources and the vast distance from manufacturer support. According to Engineering World Health (EWH), nearly 40% of critical medical equipment in developing countries is in need of repair or replacement.1 But in these areas, there are not enough trained technicians to make the repairs.

Eighty-five percent of 52 African hospitals surveyed about their medical device maintenance services had trouble finding qualified engineers locally.2 In addition, hospitals in these areas have difficulty finding and purchasing repair parts. Although a lot of organizations mean well, some of the equipment sent is too sophisticated to use or maintain. Often, equipment is shipped “as-is” without anyone checking to make sure it runs properly, or that it will even work on the electrical power in the recipient’s country. The equipment is then left for the hospital to figure out installation requirements and other details on its own.

The Challenges

In the United States, biomeds are fiercely responsible for the performance, uptime, and availability of medical devices. One of the major challenges in other countries is a lack of ownership. “US biomeds will bend or break rules, procedures, and policies, and sometimes laws, to make sure that the equipment under their care is performing dependably, accurately, and safely,” Lynch notes. “They take ownership and personalize each failure.”

In the foreign countries he has worked in, Lynch says, there is no such sense of ownership. The system, culture, or the training does not emphasize this commitment. The system is so overburdened that individuals believe that they are just another cog on the wheel and that they cannot really make a difference. “If we could develop personal drive, ownership, and accountability, the other problems of manuals, knowledge, test equipment, and parts would be solved through collaboration and sharing,” Lynch stresses.

For biomeds who choose to contribute by traveling to developing countries to help, there are a number of other obstacles as well. First, they must plan on taking everything they need to do the job with them. “This includes tools, supplies, parts, manuals, test equipment, as well as clothing and personal items,” Lynch explains. “This is a huge challenge when there are limits on the weight of checked baggage,” he adds.

Next is transportation. “If you are working away from the airport, travel can often take a day or two, depending upon distance and security conditions,” Lynch says. “In some countries, it is very unsafe to travel after dark.” Proper accommodations are another difficulty. “Most of these countries are located in the tropics, so heat and humidity are higher than we are used to in the US,” Lynch says. “Air conditioning is not a universal norm in hotels,” and food and water can be contaminated.

The problems are often magnified in healthcare facilities. Many hospitals are “open air” facilities, using open windows as the only source of ventilation. “This means that the indoor temperatures are higher than those outside. Dripping sweat while working on delicate electronic equipment is not safe,” he says. Lynch recommends bringing your own scrubs and shoe/head covers, too. “They are in short supply, and if you are large like me, they will not have the size to fit you.”

Training

Simple faults such as a blown fuse have sidelined equipment for days. Many times the repairs can be handled, but even that is not easy if there’s no access to resources or technicians haven’t been taught how to make repairs. The problem is global: The majority of countries around the world have some kind of problem with medical equipment being out of service for very basic, uncomplicated issues. However, biomedical technician training can change this situation.

Bill Teninty is a biomedical engineering technician for International Partners in Medical Equipment Training (MET). He has taught technical and management skills to hundreds of biomeds around the world. Teninty and volunteer instructors teach electronics and medical equipment repair to hospital maintenance workers. They also supply tools, test equipment, and service manuals. MET has a curriculum of six, 4-week training modules on general maintenance education, electronics, and equipment troubleshooting. Instructors are sent to places such as Haiti, Ghana, Rwanda, and the Philippines.

Teninty got his start in the late 1970s with the Radiological Equipment Assistance Program (REAP) in Southern California. His first mission was a trip to Haiti in 1980. He visited several hospitals, and none of them had anyone capable of repairing or maintaining equipment. “There were large amounts of medical equipment available, but no one to do the troubleshooting or make repairs,” he says. REAP would train nationals coming to the United States and missionaries traveling to foreign countries, but the costs of monthly room and board and transportation were high.

When REAP became part of International Aid, Teninty worked on a task force that looked at the effectiveness of this training (costs included). The result was an alternative approach: the MET program. Through this program, students are first equipped with tools and test equipment. Then come lectures, demonstrations, electronic simulations, hands-on lab exercises, and field trips to hospitals.

“It’s always best if I can find an educational partner—a school that is interested in adding biomedical equipment technology to their curriculum,” Teninty says. “One of the things I’ve always done in the training programs I’ve [conducted], is to provide a good set of hand tools and basic test equipment for a technician. If you don’t give them the tools, the training is of little use,” he emphasizes. In cases when these programs are transitioned to the local university, the expensive part of the program—providing all the students with the tools—is usually not carried on.

Building a BMET Culture

Erin Coonahan graduated from Tufts University’s undergraduate biomedical engineering program in the spring of 2012 and was working at a biotech startup in the Boston area. She was interested in gaining more experience in international development work and finding a way to combine this with her interest in biomedical engineering and technology. She applied and won a fellowship through the Whitaker International Program in January 2013. The program sends emerging leaders in US biomedical engineering (or bio-engineering) overseas to undertake a self-designed project that will enhance their careers within the field.

Coonahan subsequently learned about the EWH Biomedical Equipment Technician (BMET) program, which addresses issues with successful implementation and maintenance of healthcare technology in the developing world. Her endeavors with EWH have taken her to Honduras.

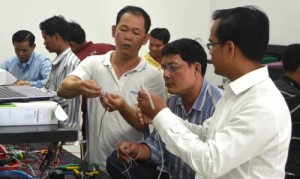

Cambodia is among several countries where EWH has helped establish BMET training programs. Photo courtesy EWH.

“Right now, I’m working on some technical manuals that will serve as the textbooks for the courses on medical equipment and include technical information and practicals for the students on how to perform preventative and corrective maintenance, and diagnose common failures,” she explains. The manuals cover equipment ranging from blood pressure monitors, infant incubators, and anesthesia machines to clinical laboratory equipment.

Coonahan is also working on finding some kind of certification for the instructors and students graduating from the program. Currently, she says, there is no BMET certification exam in Spanish, nor any certification requirement to be qualified to repair equipment in the hospitals in Honduras. “To get some sort of local or perhaps international certification for the graduates of the program would likely give them an advantage in the workforce,” she says. “The hope is that if a precedent can be set in hiring certified technicians in the hospitals, the level of quality and knowledge of the hospital BMETs will increase,” Coonahan adds.

“The lack of knowledge and technical skills for equipment repair among many of the current technicians is remarkable,” she says. The typical position is simply hospital maintenance, and a specialized position for medical equipment repair does not exist. “The technician must work on electricity and plumbing issues around the hospital as well as equipment repair, although they have not received any training in preventative or corrective maintenance for medical equipment, nor do they have the resources to perform such repairs,” Coonahan notes.

She will be in Honduras until September 2014, when EWH completes this project. The focus of the project now is on transitioning the control of the program over to the local institution, Instituto Nacional de Formación Profesional. “I’m learning about how sometimes they have to make it work here and what works best for them in this environment with smaller budgets and often without access to the correct replacement parts. The technicians here are really innovative and resourceful, and I can learn a lot from them.”

Internet Assistance

A considerable source of assistance to biomeds around the world is Frank’s Hospital Workshop, a website where biomeds can find documents about technology, user and service manuals, and training courses developed by an anonymous biomedical technician known only as “Frank.” For the last 10 years, he has provided consultations and training. “The aim of my website is to support technicians in developing countries with all my knowledge and documents I [have] collected,” he says. Based in Tanzania, Frank says he has no commercial or private interest in this project but merely wants to lend his expertise to other biomeds.

Gratifying Experiences

For Lynch, what makes the challenges of doing this type of work less daunting are the people he meets. “My fondest memories are of having a beer with the students after a week training class in Honduras and in Rwanda. Away from the pressures of class, it is great to relate with these fun-loving, intelligent men and women. They work hard, and after hours, they party hard,” he says. “It is great to connect with people of different cultures and backgrounds on a personal level. We are really all alike.”

Coonahan has learned how healthcare technology is used and repaired in low-resource settings, and she thinks this will be valuable knowledge when she returns to the United States. She’s hoping to use her experience abroad to inform her work in the design of technology for the developing world.

In working with aspiring biomeds abroad, Teninty says, “You are literally changing [students’] lives and equipping them to become an important part of their medical team at their facility.” He cites an example of the rewards of his work: After a training session in Rwanda, a student repaired several blood pressure cuffs that had been thought unusable. “As a trainer, you’re improving the healthcare of the hospital, you’re enabling the medical staff to take vital signs that they couldn’t do before. All it took was a little bit of training on how to trace down a leak and make a tube a little shorter,” Teninty says. It was that simple. “To get involved, you just need to know how desperate the needs are,” he concludes.

References

1. EWH BMET Training Program. Engineering World Health. http://www.ewh.org/professionals/bmet-training. Accessed May 6, 2014.

2. Mullally S. Clinical engineering effectiveness in developing world hospitals. Carleton University. 2008.

Nina Silberstein is a contributing writer for 24×7. For more information, contact editorial director John Bethune at [email protected].