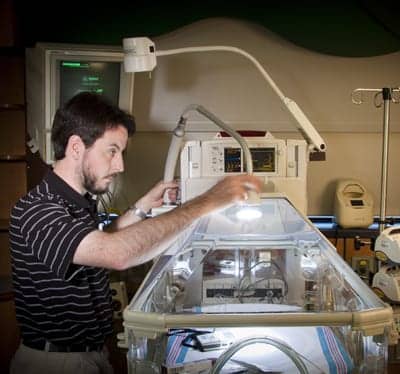

Larry Riley, CBET, performs a PM inspection on an infant incubator.

The clinical engineering team of FirstHealth of the Carolinas, Pinehurst, NC, has two philosophies guiding its activities: entrepreneurship and teamwork. Though they are seemingly conflicting, the two are actually a perfect combination for achieving the quality and service goals of the department, which are high.

FirstHealth takes quality seriously, making it part of its motto: “Working together, first in quality, first in health.” The organization publishes data on quality indicators and patient satisfaction on its Web site, easily accessible from the home page. They include the hospitals’ objectives for care, which essentially aim to match the quality achieved in the top 10% of hospitals analyzed in the comparison.

By focusing on the individual biomed as an entrepreneur and on the group as a connected team, the clinical engineering department has been able to support this effort. A restructuring of workflow guided by these principles has improved service and satisfaction. Patients are safe, clinicians are happy, and the clinical engineering team enjoys a positive work environment.

The evidence is visible in customer surveys the department routinely conducts on its own. “By and large, the results are always positive,” says Brian C. Lefler, CBET, FirstHealth’s director of biomedical services.

The high satisfaction can be attributed to the service delivered, the attitude presented, and the relationships built. Personality is as important as skill at FirstHealth. “You can train someone to work on the equipment, but you can’t train someone to be able to talk to people,” says Greg Williams, imaging engineer.

And there are a lot of people to talk to. FirstHealth services 15 counties in the mid-Carolinas. Three hospitals—Moore Regional Hospital in Pinehurst, Richmond Memorial Hospital in Rockingham, and Montgomery Memorial Hospital in Troy—offer a total of 582 beds. The network also includes the Reid Heart Center, a rehabilitation center, three sleep disorders centers, three dental clinics, seven family care centers, six fitness centers, a hospice program, home health services, critical care transport, and EMS and medical transport services.

The biomed team handles equipment at the hospitals and for the EMS and transport service divisions, as well as a number of outside clients. The total inventory is roughly 11,500. The team is comprised of 12 professionals: seven biomedical equipment technicians (BMETs) based at Moore, another technician at Richmond, two imaging engineers, also based at Moore, Lefler, and an office coordinator.

The diverse group operates well as a team, even sharing outside interests. “We believe that you can get a lot more accomplished with teamwork,” says Bryan Wallace, imaging engineer.

Individual Ownership, Satisfied Customers

L-R: Bryan Wallace and Greg Williams test the wall bucky operation of a digital radiographic system.

The irony is that the teamwork occurs so smoothly because the biomeds are encouraged to act as entrepreneurs. Each technician has primary equipment or departments for which he or she is responsible, as well as secondary segments assigned as backup. “There are some smaller departments where there may not be a backup person assigned, and we fall back to whoever can handle it if the primary technician isn’t available,” Lefler says.

Prior to restructuring to a department-based workload, the team operated on an on-call basis. “Whoever was on call for the week took the corrective calls, and so depending on who that person was, that was who the departments saw and who the face of biomed was that week,” says Larry Riley, CBET, a FirstHealth BMET based at Moore Regional Hospital.

With the new work assignment method, each technician is completely responsible for all of the equipment in his or her primary departments, both preventive and corrective maintenance. As a result, departments now have a consistent face (or two) to represent the biomedical engineering department. Customers know who to call, how to reach them, and what to expect.

At the same time, the technicians develop a more personal relationship with the departments, which has a beneficial impact on service. “Communication and information exchange is a lot easier, and this contributes to the positive results on customer surveys,” Riley says.

The advantages make up for the extra managerial work involved, according to Lefler. He instituted the structural change when he first came on board and, initially, spent a lot of time matching interests and backgrounds with departments to evenly divide the workload. “In some departments, we had one technician who already had a good rapport, so they were a natural fit. But, there were areas that were not as popular and just had to be assigned,” Lefler says.

Lefler continues to monitor assignments to ensure that the experience is spread around the team and the workload is balanced. “It’s a lot of data analysis, but the benefits outweigh the drawbacks,” Lefler says, noting ownership is the biggest benefit. “When you assign work on a departmental basis, you entitle that technician to become something like an entrepreneur,” he says.

Scheduling Freedom, Balanced Workloads

Matthew Hunsucker evaluates a video fiberscope.

The entrepreneurship stems from the ownership. Each biomed is responsible not only for all maintenance related to their primary equipment but also for scheduling that maintenance. The PM calendar is created with an eye toward balancing the workload throughout the year and to the individual’s personal preferences. The effort, completed collaboratively between each technician and Lefler, involves utilizing information from the team’s clinical equipment management system and paper plotting.

The first step is to print out the PM requirements for all of the equipment under a technician’s purview. Each device is given a rating to indicate the PM frequency. The technician then decides when the PMs will be due. For instance, if the biomed knows he will be taking vacation in July, he can schedule a lighter month in terms of PM deadlines.

Everything is scheduled in this way, including the outside clients, clinics, and EMS and transport systems. “We have to visit the EMS bases twice a year, so we completed PMs at the regional transport bases in January and February and will do those for two of the EMS bases in March and two in April,” Riley says.

The only challenge is to ensure coverage while out at the sites—but with a backup to call on, the challenge is less severe. And, knowing that he’ll be out in the field, Riley can avoid scheduling a lot of other PMs at the hospital in the same month.

The imaging team works in a similar fashion, splitting their workload up by facilities and quarters: one hospital per the first three quarters and the rest of the customers in the fourth. Of course, priority goes to corrective maintenance. “When you have an x-ray room down, you don’t have another to put in its place while you’re working on it. So if a machine is down, the PM on another machine will have to be set aside,” Williams says.

Managing Resources, Choosing Contracts

The equipment at FirstHealth is a blend of old and new. Clinical engineering will provide input to administration regarding end-of-life equipment issues and capital investment, but if resources are limited, the team will use third-company refurbished parts to keep older devices running.

Like clinical/biomedical engineering departments at many hospitals, the team aims to cover as much in-house as possible, as long as it makes fiscal sense. “We look at how much the contract is going to cost versus how much it costs to cover in-house,” Riley says. “Sometimes, it’s pretty close. If it’s going to take up too much of our time for the same cost, our time can be better utilized working on something else.”

The team will consider all of its options. “If we don’t do a contract, can we do it ourselves? And if we can do it ourselves, are there any local third parties we can utilize, or can we use a manufacturer on a time-and-materials basis?” Lefler asks.

In most cases, the department has decided they can take on the work. Its main service contracts cover large analyzers in the clinical laboratories, CT, MR, and the cath labs, though Williams and Wallace have been looking into taking on CT. “CT is pretty much the same animal as any other imaging field, but MR is a particular, specific field that we really haven’t had any training in,” Williams says.

Constant Training, Cross-Training

Marty Davis completes the reassembly of an ultrasound system after repair and testing.

The imaging team does have some coursework lined up, but it has had a difficult time finding the time to take advantage of it. “The hospital is definitely behind us and wants us to be trained,” Williams says.

The “gold standard” for training is vendor schools negotiated into the acquisition price. “But that’s not always feasible, so we have utilized third-party training quite a bit,” Lefler says, citing ultrasound machines, contrast injectors, and flexible scopes as examples of third-party training.

Cross-training is another excellent solution for appropriate equipment. “It has always been a policy in the shop that only those who have been trained by the manufacturer can work on life-saving equipment,” says Marty Davis, the FirstHealth BMET based at Richmond Memorial. However, devices with lower risk profiles can be taught through cross-training.

Recently, the team sent a few technicians for training on a new telemetry system. When they returned, they shared basic information learned in the class with everyone. “They gave us training that did not include everything they had learned, but enough so that we can respond if called in at night,” Davis says. “We know how to get to the service menus, reconfigure the boards, and change out a CPU.” With the telemetry system throughout the hospital, everyone is expected to have related equipment in his/her areas and will, therefore, benefit from the knowledge.

For similar reasons, most of the team has also had some sort of IT training, at least one basic introduction to networking course. Some have completed more formal coursework and obtained certifications, such as Network+ (covering networking) and A+—proving competence in areas such as installation, preventive maintenance, networking, security, and troubleshooting. “The goal is to get as many people A+ and Network+ certified as possible,” Lefler says.

The education is useful in a world where equipment is increasingly networked. “A lot of our patient monitoring is starting to run alongside the hospital’s standard IT network, so we have to connect with our IT department more now than we ever have,” Riley says.

Teaming with IT

There are few barriers to the cross-departmental collaboration, particularly since both groups report to the chief information officer or CIO, a recent change in response to administrative restructuring. The clinical engineering department used to report to the vice president of professional services. “[The new arrangement] was a natural fit and made a lot of sense for obvious reasons,” Lefler says.

The change was seamless from the team’s perspective. “We didn’t really notice any changes,” Riley says. The two groups had already been working together on various projects. One such effort involved a new monitor installation. The biomedical department worked with IT and Cisco Systems Inc, Torrance, Calif, to enable the system to run wirelessly on the hospital network when patients are under transport. “If it’s hardwired, it runs on the monitor network,” Lefler says.

The unique solution allowed the hospital to avoid having to pay for and install a redundant wireless network to handle the monitors. “It was a nice way to save money and a nice way to partner with IT,” Lefler says.

Lefler also worked with IT to set up a dashboard tool for the department’s computerized maintenance management system (CMMS). The dashboard displays key performance indicators in real time using easy-to-understand graphics. “I’m logged in every day and can see things like the PM status for the month or open work orders. I don’t have to go into the CMMS, run reports, and analyze data,” Lefler says.

Constant Monitoring, Consistent Service

L-R: Greg Curtis, Donna Caviness, Baxter Williams, and Brian Lefler discuss a work order.

A quick glance at the dashboard lets Lefler know how the team is doing, but communication is also key. The team meets regularly on Tuesday mornings via conference call (Davis does not make the 32-mile drive to Moore from Richmond) and once every few months face-to-face.

During those meetings, information is exchanged regarding upcoming projects, particularly so that those with backup and on-call assignments remain up-to-date. “Typically, they last about 30 minutes,” Davis says.

Team members will often also meet with Lefler individually on a monthly basis to review their work and customer feedback. Generally, the news is good, and if for some reason it is not, it is immediately investigated and easy to track.

In the past, the team would send out annual surveys to customer departments for input on service and quality, but this type of program can mean the survey responder has forgotten details (including who the biomed was) or that the response is too late to matter. Now, the office coordinator sends out surveys monthly.

Two work orders are picked at random for every technician (“we’re working to automate this step,” Lefler says) and sent to the customer along with a four-question survey: was the response timely; was the technician courteous; did he fix the problem; and overall, what did you think. Replies are rated on a four-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

The data is stored in a spreadsheet so that individual technicians can be properly evaluated. “We don’t get a lot of negative feedback. Everything has been very positive for the past several years,” Riley says.

If there is a problem, the issue can be easily researched and resolved immediately. Here again, ownership is key. “Everybody is enabled and expected to manage their customer. If the customer is unhappy, the technician is responsible for repairing the situation,” Lefler says. “The survey is just a mechanism to make sure that everything is going well.”

Happy customers have led to outside work. What started as a joint venture of FirstHealth’s has expanded into a small client base for the biomed team. In fact, some clients first reached out to FirstHealth when they needed a more immediate response than their manufacturer could provide. “We’ve got several doctors’ offices and surgical clinics very nearby. They can call us, and we can show up pretty quickly, usually within a day, sometimes within an hour,” Riley says.

Though the program does not generate a large amount of revenue, it does show a profit. However, the bigger benefit is the marketing value, Lefler notes, saying, “It has put FirstHealth in a positive light.”

The clients benefit from faster service. If any of the biomeds run into trouble, they know they can call anyone on the team for help. “If I’m on call and am struggling with a piece of equipment, I can call the person whose department it is, and they can talk me through it. You hate to do it, but everyone understands—we work together,” Davis says.

The combination of teamwork and entrepreneurship makes the FirstHealth clinical engineering department a responsive, consistent, and high-quality team as well as a unique one. Everyone values this quality, from the customers to the biomeds, including Williams, who shared, “It’s a great working environment. I’ve worked at several places, and I’m enjoying this a lot.”

Renee Diiulio is a contributing writer for 24×7. For more information, contact .