|

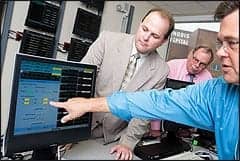

| Joe Flick, manager of biomedical operations (far R) explains the functionality of the new patient monitoring telemetry room, designed by Project Manager Pat Guinle (middle), to Jeremy Cook, corporate director of clinical engineering (L). |

A biomedical engineering shop with designs on pleasing its customer base is not altogether uncommon. But one that puts as much energy and focus into pleasing its techs just might be.

“I take my associates’ satisfaction very seriously, because in the biomed world that is the driving force of what saves my organization operational dollars,” says Jeremy Cook, corporate director of clinical engineering, Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare, Memphis, Tenn. “Most of what you spend your budget on is not labor, it is not your associates’ benefits—it is actually on the parts and everything that goes into the actual repair. So if you train your associates really well, they can save you a lot of money on parts and service by doing the work in-house; instead of what you would have spent on outsourcing to either the OEM or a third party. And if you keep your associates happy, they will stay with the organization after you train them.”

Cook has always believed that, “As a leader, your team is what makes you great; you just have to serve them so that they can be all that they want to be.” He believes that building a successful team requires a few basic components: train your team well, pay them what they are worth, and treat them like professionals. The formula is working. During his tenure, job-satisfaction survey results from the clinical engineering department’s 30-plus associates have risen to a score of 4.28 on a five-point scale. It is one of the higher-rated departments at Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare, which includes seven hospitals and multiple imaging and surgery centers.

“This happened by my listening to our associates and asking them to tell me what would make their job easier and more efficient,” Cook says. Part of it was also understanding that, while dedicated to their jobs, the associates also have lives and interests outside of the medical centers. “My associates know that they have a pool of customers they are serving, and their schedules are based off the needs of their customers.”

By the same token, “That flexibility also goes both ways,” he adds. “I work with them, so if they need time off with their family, for example, I’m flexible with that.”

That level of respect is recognized and appreciated by the team. “In the 18 years I’ve been here, the philosophy of this hospital has always been to treat everyone as an equal, and it’s not just talking about the core values. They actually mean it,” says Elvin O’Neal, diagnostic imaging engineer II. He explains that, as part of the hospital’s aim of creating an equitable work environment, every employee has the same right to voice his or her opinion—regardless of job title. “It doesn’t make a difference here if you are [an executive] or a floor sweeper. They give everyone the same respect, and that has made all the difference in the world.”

Working as a team is also more than just talk for Cook, according to Joe Flick, who is currently Methodist’s manager of biomedical operations.

“I’ve been on jobs where I need some help, and when I call Jeremy, instead of him sending someone out to help me, the next thing I know, in walks the boss with his shirt sleeves rolled up and a toolbox in hand,” he says. “So, the working relationship and respect isn’t just between the biomeds; Jeremy is also a part of that.”

Teaching the Ropes

For Methodist, as with any biomed team, up-to-date and thorough training is essential to success.

|

“We get practically all the training opportunities we want, and that creates just a really good working environment,” Flick says. “It allows us to grow professionally, as much as we want to, and that helps us build confidence in ourselves at the same time.”

Having the know-how required to manage a variety of tasks also sets the biomeds up for success. “Whenever you take a job, you are in charge of completing it and doing that job on a day-to-day basis,” O’Neal says. “They give you total leeway to do it to the best of your ability, and that means everything from flexible schedules to providing the tools we need. And that is the one particular thing the biomeds really like, because it puts you on a professional level.”

Techs returning from formal training are also required to cross-train their peers, ensuring that the knowledge is shared throughout the entire department. Another training requirement takes the “team effort” to a new level.

“If one of my associates wants to be promoted to the next level, they have to train another associate to do their job—and to do it as well or better than they did—before they can move up, because our department is not going to go backward in our service expertise for a specific area, or site, or specialty of equipment,” Cook says. “And the associate also knows if that person replacing him or her fails to perform that job to that level, he or she will have to refill that role, which slows their developmental and professional growth.”

This straightforward approach—as well as the structure of the department—not only encourages professional development through direct training and management experience, it also provides additional exposure opportunities within the department.

“We actually have our radiology and biomedical engineering divisions reporting to the same person, which allows a biomed to say, ‘If I’m here long enough and I prove I can take care of my customers and provide great service, then I know my skills will be recognized and I will be trained for and promoted to higher-paying jobs, like working on x-ray, or CT, or MRI,” Cook says.

What do the biomeds think of this approach? “It was designed off the mentoring program and then was turned into a continuous education program,” O’Neal says. “But essentially, what you do is, you make sure that the strengths and skills that your department has gathered stay in the shop and are given to all associates in the team. That’s what it’s all about.”

Flick also believes this “give to get” practice is all part of a bigger picture emphasizing the shop’s policy of sharing, rather than hoarding, knowledge and skill sets. “It’s a win-win situation,” he says. “For the guys who have been here a little longer, they are essentially always training their replacements, whether they know it or not. And, in turn, it’s giving that new guy the opportunity to move up within the department. In the end, it’s going to make them both more money, give them both better job satisfaction, and—for our customers, patients, and nurses—it’s going to give them all-around better technicians and engineers.”

Striking a Balance

With a health care network that includes numerous hospitals, surgery facilities, and imaging clinics, the list of acquisitions, upgrades, and improvements is bested only by the list of necessary maintenance and repairs. And, to paraphrase a popular management philosophy, it’s impossible to improve what isn’t measured. For Methodist, whether or not the team is meeting the department’s operation goals is measured by a set of customized key performance indicators (KPIs).

According to Cook, Methodist initially evaluated the benchmarks used by other organizations and eventually decided to create its own rulers. As a result, he says the KPIs in place at Methodist are far more stringent than those at other institutions. For example, Methodist has its own definition of “downtime.”

|

| Elvin O’Neal, diagnostic imaging engineer II, makes adjustments to a Siemens E-cam nuclear medicine camera. |

“From our standpoint, if you can’t use a machine or an instrument 100% as advertised, it is considered to be down,” Flick says.

O’Neal adds, “A lot of times people will only measure downtime by a complete system failure or by loss of functionality during working hours, but the way we do it reflects the reality of a piece of equipment and the impact its performance has on our customers.”

That reality is a good one for the hospital, which currently enjoys a systemwide uptime around 99%. These standards do not allow any leeway, even for machines that are inaccessible. “My direct report understands that he can’t take my KPIs and compare them with the vendors, because my standards are much higher than those set by the vendor,” Cook says.

Another example of these rigid guidelines is the KPI for the average repair turnaround time, which is just 3 days regardless of reason or equipment type.

“What our system has said is that in 3 days, on average, you should be able to get the equipment repaired and back to the customer for use,” Cook says. “The intention is that the shorter amount of time something is in the repair process, the less equipment you actually need to purchase on the front end.”

This edict was made with a caveat: “They told me to hit the goal without spending an egregious amount of money; because, of course, I could just overstock parts to try and hit the 3-day goal,” Cook says.

In the year since the repair turnaround KPI was introduced, the average has dropped from 6 days to less than 5. The improvements are due in part to the proactive approach to the work, in particular their diligent attention to preventive maintenance (PM). The PMs, of course, are also gauged using KPIs.

For Methodist, the goal is a 95% PM completion rate, on time, as well as a 100% completion rate, year-to-date. As of September, the team was about 1% away from its on-time goal and just over 3% away from the year-to-date goal.

In addition to providing an overview of the department’s job performance, these stringent measures foster a proactive approach to the work, encouraging the engineers to examine ways to reduce the overall call volume by preventing systems from ever failing in the first place, according to Cook. This can include everything from adding tasks to the PM procedures when the system is in the shop for a scheduled downtime, to scanning and cleaning databases in an effort to preempt software crashes.

According to O’Neal, another way they are working to reach the downtime KPI in some cases is to “almost double the normal PM schedule, so if the OEM suggests to do it every year, we may do it every 6 months.” Doing so not only minimizes downtime, but it can also extend the life of the equipment. “When you do the PMs more frequently, you are more likely to find, for example, a frayed cord which, if left unattended to, could cause a short or some other big issue with the system.”

Marking more PMs on the work schedule is sometimes argued as a waste of resources; not so, according to Flick.

“I have heard all the arguments pro and con, including the use of 10% sampling, but our standpoint is, if I am that patient, do I want to be treated on a piece of equipment that is included in the percent that was never tested?” he says. “For us, what is more important than saving some time is being able to feel comfortable with that piece of equipment being attached to one of your loved ones.”

Tough though they may be, the KPIs serve as motivating factors for the biomeds. “The KPIs don’t affect our job; they are our job,” Flick says. “But it’s more than just what drives the work; it’s our benchmark on how we rate ourselves.”

O’Neal concurs. “It’s like our report card, and it gives us great feedback, because you get a picture of the whole entire system and how well our shop is performing overall. We are a team; each one standing with the other.”

Key Players

In addition to regular training and meticulous attention to maintenance schedules, meeting some of the group’s ambitious goals—particularly those involving money-saving initiatives—are feasible through the efforts of the department’s dedicated project manager, Patrick Guinle.

The project manager’s job is twofold, according to Cook. For capital acquisitions and other sizable projects, such as the hospital’s recent replacement of telemetry monitors, he will meticulously review vendor quotes to determine which items can be eliminated from the contract or can be purchased from a third-party vendor at a better price. He also maintains a familiarity with the health network’s stock of unused equipment, to identify where available (and already-owned) items can be incorporated into a new project or acquisition.

“By doing those two things, he can scale down a quote pretty considerably,” Cook says. In fact, in the last year, the project manager has helped the biomed department save or delay capital expenditures in the amount of $1.1 million. More than $100,000 was saved just in the order for the new telemetry system by axing unnecessary items. Still, the project manager’s focus isn’t solely on cutting numbers. “He evaluates all aspects of the project, and in some cases we will upgrade part of it because in the long run it will be better for the hospital and its patients. It’s not always about saving money. It is about getting the right order placed with the vendor.”

Because a project manager sits on the staff, the biomeds are freed from the balancing act that many engineers find themselves performing between projects and service.

“Having a project manager increases that level of expertise,” Flick says. “As a biomed, or a diagnostic imaging engineer, we are really good at what we do. For the project manager, he is really good at that. Because I’m not as practiced at project management, I might overlook something as simple as, what does our power rating have to be for a particular piece of equipment we’re looking to buy or do we have enough network drops, for example.” He adds that not having to split his time improves his quality of work.

While responsible for making recommendations, the project manager works closely with the techs when deciding what systems and equipment to purchase—a collaboration made easier by his years of experience as an engineer. For shops considering the addition of this type of position, Cook recommends securing a highly experienced biomed.

“The project manager was born out of the shop,” O’Neal says, who believes it’s critical that anyone holding this role be a seasoned biomed. “That way, they realize the most valuable information. They know the equipment and how it impacts patients, and how the biomed world works overall, which is something you can only get from being a biomed.”

“They need to have been in the field at least 10 years so they can comprehend the different dynamics involved, because the projects are going to vary widely,” Cook says. With the right person, the position can pay for itself. “For a long time, this role was part of the engineers’ regular jobs, but their time was divided between trying to make repairs on systems and trying to deal with projects at the same time. This way, we can empower everyone to perform their jobs to the best of their abilities.”

Dana Hinesly is a contributing writer for 24×7. For more information, contact .