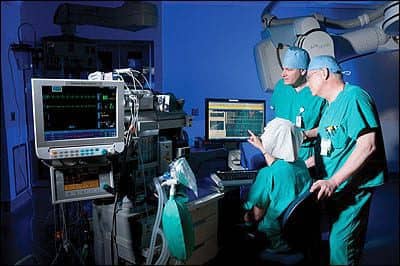

L-R: Steve Pohlman and Robert Macher (foreground), work with Jerry Smith (seated), to verify that patient monitor data is received and reported in the anesthesia medical record.

Dan J. Hare, CCE, director of clinical engineering with Mercy Clinical Engineering Services at St Luke’s Hospital in Chesterfield, Mo, recently analyzed some numbers that biomed departments do not regularly crunch—years of experience. Adding the figures for his 10-person team, some of whom are shared with local competitor St John’s Mercy Medical Center (located in nearby Creve Coeur, Mo), Hare found the group has more than 220 years of experience combined—nearly a quarter of a millennium. “Of that cumulative experience, 124 years, or 57%, has been served here at St Luke’s,” Hare says.

Needless to say, the turnover rate is low (the “newest” technician was hired 3 years ago), a fact Hare credits to the facilities for being great places to work. In fact, St Luke’s has been recognized as “A Best Place to Work” and as a HealthGrades “Top 50 Hospital” for the past 5 years. The arrangement of shared resources, in terms of clinical engineering services, has benefited all parties. The hospitals save money, Mercy generates revenue, and the clinical engineering team can shape their careers to fit their interests.

Many are able to specialize in the equipment areas they find most interesting, though team spirit is also required. “We need to be able to address the problems of all items out there, but we also need people to become our experts on individual items,” Hare says. “So we have to be both a jack of everything and a specialist in a few areas.” New employees may start as generalists and eventually become specialists in a chosen area, or the department may hire them to cover a specific type of equipment right off the bat.

Whatever the path, their endeavors are supported with significant training, in-house mentoring, defined roles, and a certain measure of independence. The institution’s clinical engineering departments have assumed control of associated responsibilities, such as handling budgets, managing contracts, and coordinating schedules, particularly for preventive maintenance (PM). They do such an efficient and satisfying job, that St John’s and St Luke’s opted to continue the shared services despite a decision to split as business partners.

“The beauty of the arrangement is that we share assets, with the ability to access resources at each organization, but the facilities are still independent financially. So, we’re kind of a for-profit outsource for not-for-profit institutions,” Hare says.

Amenable Arrangement

The arrangement first began in 1999, when a number of area hospitals partnered to compete against booming HMOs, forming their own group called Unity Health. The clinical engineering departments (and a few other groups, such as information services, or IS) consolidated to create a corporate service, Unity Clinical Engineering Services, that worked within all of the institutions.

Around 2005, however, the partnership began to dissolve, and eventually, all of the hospitals disbanded, returning to solo operations. St Luke’s and St John’s Mercy were the last two to part ways, but both decided to continue purchasing their clinical engineering services from St John’s Mercy’s parent organization, Mercy. With the dissolution of Unity Clinical Engineering Services, it then became Mercy Clinical Engineering Services. The two hospitals compete in every other regard, but share certain clinical/biomedical engineering personnel and occasional equipment when needed.

The arrangement means that both institutions have greater access to specialized biomed talent. “Neither organization, in a sense, could afford to have some of these specialty people 100% of the time,” Hare notes. The volume of equipment would not justify their concentrated focus, resulting in a waste of personnel dollars, biomedical expertise, and scheduling conflicts.

CE + IS

Of course, it was not always this way. Back in the day, the clinical engineering department at St Luke’s offered whatever service it was capable of as part of its general care of technical equipment.

Dave Weiskopf (left), explains the repair strategy for a SPECT nuclear camera to Dan Hare.

“Anything with a wire came under our purview,” says David Kelly, BMET III with Mercy. He has been at St Luke’s, wearing many different hats, for 32 years. In his earlier days, the biomed department handled requests that dealt with filming or videotaping as well as early efforts to computerize records.

“It was the old mainframe terminal type of arrangement, and, aside from contractors pulling cable, biomed handled the cabling, interfacing, and terminal and printer repair,” Kelly recalls. With the consolidation into Unity and then Mercy, those responsibilities were split between clinical engineering and IS. “IS took over a lot of the stuff we used to do, but we have continued to have an extensive relationship with them,” Kelly says.

Like clinical engineering, IS has a number of different specialists on its team—such as integration, interface, application, desktop, and network—each of whom may eventually need to be called upon for help. “You will have to deal with all of these people at some point, whether it be setting up equipment, getting connected to the network, or resolving application issues, so we maintain a tradition of collaboration,” Kelly says.

This relationship helps to determine the proper contact and to obtain their help. One challenge many biomeds note when dealing with IS departments is the lack of urgency related to fulfilling patient care needs. “They’re not always aware of the importance of real-time response to issues,” Kelly says.

In addition, a collaborative arrangement helps to blur the line between responsibilities and maximize the use of resources, resulting in better customer service. For instance, “We had some systems that went down last week,” Kelly says. “We were called first and verified our equipment, but worked with IS over several hours to help them reset their interfaces. We could have just said, ‘Our stuff’s working,’ and walked away, but we wanted to help our clinical users get served.”

Similarly, the biomed team has taken steps to back up systems so that when problems occur, they can get equipment that has gone down up and running quickly. “As everything moves more and more toward PC-based systems and modalities, the biggest fear is a hard drive crash or something similar,” Kelly says. “So, for our mission-critical systems, we’ve cloned the hard drives to have on hand if something happens.” The process is fairly inexpensive, and the peace of mind, priceless.

Clinical Clout

The Mercy Clinical Engineering team has a lot of control to put into place procedures that it finds beneficial to performance and customer service. In addition to being able to add protocols, such as the hard drive cloning, the team also handles budgets, contracts, and schedules.

“We have control of all service dollars and support for anything medical, which gives us the ability to manage it properly,” Hare says, contrasting this policy with organizations where departments, such as radiology or the clinical laboratory, manage these funds internally along with the subsequent service contracts. In this way, the clinical engineering department can better manage “the peaks and valleys that happen with each modality” and more appropriately adjust contracts.

In general, Mercy Clinical Engineering for St Luke’s and St John’s aims to keep as much service and repair in-house as possible, although the team makes use of all the types of service agreements (full-service, time-and-materials, third-party, in-house, and hybrid). “Not one model is always perfect for every organization or every item, so we vary them,” Hare says. “But rarely do we have full-service contracts because we want to find a way to keep the dollars here as best we can.”

Departmental Teamwork

One of the ways the team has been able to complete so much service in-house is through the specialization of team members. With more than 8,000 devices in the inventory, no one biomed can service them all—although they will try if needed. “We all share at some point,” says Dave Weiskopf, a radiographic equipment service technician (REST) III with the Mercy team.

However, each biomed also has the opportunity to pursue a specialized area. Specialization has been found to increase customer service at the same time that it has pulled in greater user participation. Stephen Pohlman, a BMET III with Mercy Clinical Engineering Services, has been handling the anesthesia-related equipment for both St Luke’s and St John’s since he first came on board in January of 1999. The inventory includes 33 anesthesia systems with monitors at St Luke’s; 55 anesthesia systems at St John’s Mercy Medical Center; 11 at St John’s Mercy Hospital in Washington, Mo; and four anesthesia systems at a surgery center associated with the Creve Coeur St John’s Mercy. Pohlman also covers recovery room monitors, GI anesthesia monitors, and perfusion equipment. Working closely with the facility anesthesia techs, Pohlman is able to handle the entire inventory with downtime minimized.

“I’m the only person who does what I do, and I work very closely with the departments and the anesthesia techs,” Pohlman says. The focus has allowed him to develop the expertise to not only handle service in-house, but to also train the anesthesia technologists in early troubleshooting.

“The anesthesia techs are really the first string when there’s a problem, and usually, they are able to take care of it,” Pohlman says. “I don’t hesitate to train [the anesthesia techs] or teach them how to do something because sometimes it will be a problem that happens in the middle of a case, and they’re right there. I’m not always on the scene to get called into a room.” He spends the majority of his time at St John’s.

Training is not “official” and ranges from one-on-one sessions with new employees to informal in-house services addressing more widespread issues. Pohlman aims to cover as many troubleshooting skills and processes as appropriate.

“We’re very fortunate in that [the biomeds are] willing to share information with the anesthesia techs, and they’re pretty much, for the most part, willing to learn and take on additional responsibilities,” Pohlman says.

Plans A and B

Tom Ackman assists Dave Kelly (kneeling) with a hemodialysis system overhaul.

Sometimes, the solution may be swapping out a piece of equipment, such as a module, cable, or even an entire machine, but downtime is minimized whichever way. The number of assets and level of trauma (level two in most cases) offer a small, but significant, bit of flexibility in completing repairs. “You don’t have really hard-core problems every day—maybe once a week or every 2 weeks—but we’re very fortunate to have spare equipment so that they can set it aside and it can wait a few days,” Pohlman says.

If the anesthesia techs cannot troubleshoot the problem based on this training, they can call Pohlman for advice. “I’ll try to talk them through it over the phone, and they’re pretty good at it. But if it’s necessary, I can usually be at St Luke’s within an hour,” Pohlman says, noting when he arrives he is jokingly referred to as the “heavy artillery.”

The result is that problems tend to be addressed immediately. “We have very little downtime because when the anesthesia techs tell me what the problem is, I can usually solve it and get them up and running relatively quickly,” Pohlman says. Even when he is not available, such as when on vacation or sick, equipment can wait until he returns.

“There’s always a plan B,” Pohlman says. “They may have to shuffle equipment around until I get back, but if we were going to call outside service, it usually takes them 2 to 3 days before they get here anyway. Sometimes, it’s a week.”

The process works out well, and Pohlman enjoys his role. Even though his scope is limited, he is never bored and is always challenged. Downtime is minimized, and the departments are happy. He contrasts this with the possibility of having two people on the anesthesia equipment along with other devices. “We’d each be spending half of our time doing other things outside anesthesia and would not be as good at maintaining the equipment as a dedicated person,” he says. Even completion of PMs goes more smoothly. “I’m always up-to-date, and in anticipation of the busy months, I’m actually able to get a head start,” Pohlman says, noting that if they are not finished on time, he is the only one to blame.

Developing a Forte

“The advantage of specializing is that you can get good at it—jack of all trades or master of none,” says Rick Millard, a Mercy REST III based at St Luke’s. He acknowledges that there is some crossover service required, but that specialization results in greater productivity for the biomed. Millard also works with the department (his area is imaging) to manage affairs, reporting that the PACS administrator acts as the go-between for the devices, the servers, and IS on many problems.

“We work very closely with him when new equipment comes in or when we have to reconfigure,” Weiskopf says, who also specializes in imaging equipment. “We will go straight to IS if there are issues, but the products have matured so that we don’t see the problems we saw 5 or 10 years ago.”

Steve Kaupas repairs a patient monitor.

Weiskopf estimates that he and Millard work on approximately 50 imaging devices and another 100 to 150 peripherals. Two other shared biomeds cover CT and linear accelerators (linacs). Since they are not always present, Weiskopf will take the first call on the CT and all calls on the peripherals; he also services the cath labs, nuclear medicine devices, and digital mammography units. Millard focuses on MR and the x-ray rooms.

There are some service contracts in place. “We do use some shared-service agreements—lower-level agreements—on some of the equipment I maintain, which makes it much easier for me to use their resources, though I rarely have to call for outside help,” Weiskopf says. Millard also seeks to avoid calling the vendor whenever possible.

Even so, imaging is often where contracts are used. Often a vendor is called because the team lacks resources, whether time, tools, or technical expertise. “Typically, imaging is going to make up well over 50% of your budget with just a few items, so there is huge opportunity there to manage a lot of dollars,” Hare says.

In-house support not only saves contract dollars, but also minimizes downtime, protecting patients along with revenue. “We look for the best value, and that doesn’t always mean the best price,” Hare says. “We want to make sure a service request is addressed in a timely manner to ensure minimal downtime, eliminate interruption of patient care, and maximize customer satisfaction.”

Decisions are made on a machine-by-machine basis with individual cost analyses that take into account many different factors, including training expenses and device history. Sometimes, it is a balance, and sometimes, it is a gamble.

“The last several years, the hospital has been going through a period of equipment acquisition and replacement,” Weiskopf says. “So, we’ve seen a lot of the oldest systems go and new systems come in. With that comes a change in the way they are serviced.” Their reliability often rises, but it becomes more difficult to find less expensive parts outside of the manufacturer. “So while the incidence of failure goes down, the cost of parts has increased,” he says.

Shared Knowledge

Similarly, new equipment in small numbers can present a challenge to expertise. The team will always negotiate training, but if the systems do not break down often, it becomes difficult to expand one’s knowledge, abilities, and speed. In some instances, the training is not even deemed worth the expense, however discounted.

The recent purchase of a new room in the operating suite would have required weeks of training at a cost of $40,000 to reduce the service contract fees. “With one room, we probably would not have made that $40,000 back,” Hare says. “Whereas, when we have more systems, it makes more sense to spread the cost of training and create support for many rooms.”

Of course, not all training is formal. Robert (Bob) Macher, a BMET III who services a range covering roughly 1,700 systems at St Luke’s, will often give new employees a “lay of the land.” He reviews how things are segregated and early troubleshooting; when new equipment comes into the shop, people are generally curious and gather ’round.

With the wealth of experience on the team, cross training and mentoring are standard, not only among the biomeds but between biomeds and the staff they work with. “Any of us is willing to share what we know, but there’s not a big turnover,” Millard says, highlighting the team’s cumulative quarter millennium of experience.

Renee Diiulio is a contributing writer for 24×7. For more information, contact .